The Economics of Militarisation

Kashvi Singh

All throughout history, military power has remained at the

core of world politics, but are we to see this change in the 21st

century? As we begin to focus our attention on global trade and cooperation,

would the incentive to build mighty armies shrink? Or will military power still

dictate a nation’s level of influence in the global political sphere? There is

good reason to believe in both.

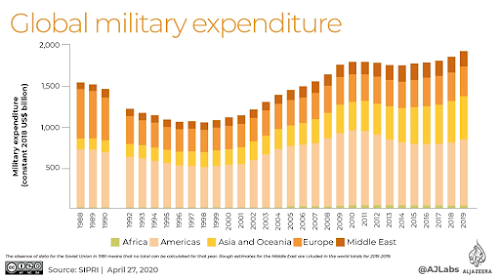

With the resurgence of the nuclear arms race, the unending conflict in the Middle East, Russia’s ambitious military policy, and an overall increase in global military spending, the path that world leaders have chosen for the future of militarism becomes evident to the extent, that whether or not economic interdependence can prevent future military action becomes uncertain. Advocates for militarisation would defend this on the grounds of financial gains that are extracted from the military, which can undoubtedly, be an asset to a nation’s economy. The main contribution of the military sector to the economy is the provision of jobs. As of 2019 for example, roughly 0.2% of the UK’s population was directly employed by the defence industry. Furthermore, some argue that even though military expenditure might not improve GDP levels directly, it helps the economy by reducing risk and by providing political stability.

However, one must

understand the enormous opportunity cost involved with spending large

proportions of a nation’s GDP on the defence sector. The first and the most

obvious being the misuse of financial resources available, as many nations

prioritise spending for military over other necessary sectors that contribute

directly to the quality of life. An extreme but nonetheless relevant example of

this is North Korea. Last year, North Korea ranked No.1 in military spending as

percentage of GDP. “According to the State Department's World Military

Expenditures and Arms Transfers 2019 report, the North's military expenditure

averaged about US$3.6 billion a year. That accounts for 13.4 to 23.3 percent of

the country's average GDP of $17 billion during the period 2007-2017.” At the

same time, reports of North Korea’s crumbling health care sector [1] show how prioritising military spending over other essential services can

damage the standard of living in the long run. To put things in perspective,

money that is used for the production or purchase of armaments is money that is

not available to vaccinate children against disease, to provide people with

clean drinking water, to assist local industries or to supply credit to local

farmers. So, while nations sign arms deals worth billions of dollars, the World

Health Organisation remains underfunded to carry out crucial programmes in

EDC’s and LIDC’s.

Another problem with

prioritising military over other sectors is that of Research & Development.

A study by ‘Project Ploughshares’ finds, that more money is spent on military

R&D than research into energy, pollution control, health and agriculture

combined. In a world that is often urged to cooperate and work together to

tackle global issues such as environmental degradation or world hunger,

militarisation which is often also the root of these problems, comes in the way

of solving them too.

Moreover, military finances also aggravate the problem of

debt in developing nations. 25% of the debt that is owed by the developing

world to the developed world, accounts for arms imports. This debt not only

burdens these nations economically, it also directly affects the already

crippling health and education systems, leaving governments with hardly any

revenue left for welfare spending to support sustainable development, while

also preventing inward investment into businesses that might help support the

economy.

While it is obvious that nations are not willing to give up

the concept of militarism any time soon, we must realise that the consequences

brought about by militarisation far outweigh its so-called benefits. Excessive

funding to military not only disrupts peace, but also prevents sustainable

development by depriving other essential sectors their due share of investment.

References:

Comments

Post a Comment